For most of the last decade, healthcare interoperability has been framed as a technology problem.

We told ourselves to standardize APIs.

Then, to adopt FHIR.

Next, connect more networks.

And finally, to simply move faster.

And to be fair, enormous progress has been made. We now have national frameworks like TEFCA. We have patient access APIs supported by information blocking. We have identity vendors, consent tools, and nationwide exchange networks connecting tens of thousands of organizations. Doctronic will now refill certain medications for patients in Utah. And ChatGPT Health can connect your medical records to enable more personalized health AI interactions.

Yet meaningful, frictionless data sharing at scale still feels out of reach.

Not because the pipes are broken, but because trust is.

The Policy Triangle We’re All Living Inside

Today’s health data exchange environment operates inside a policy triangle:

On one side, HIPAA permits, but does not require, data sharing for treatment.

A second dimension comes from Information Blocking regulations, which shift the posture from “you may share” to a general expectation that “you will share.”

The third side is TEFCA, introducing contractual obligations that define when participants must share under common rules and network expectations.

So we now have:

- One regulation defines when you’re allowed to share.

- Another establishes when you’re expected to share.

- Contractual agreements specify when you must share.

If that’s the case… why does exchange still slow, stall, or fail in the real world?

Two realities explain more than we often admit:

Trust among strangers.

Ambiguity about responsibility.

Interoperability is no longer happening only between familiar institutions with long-standing relationships. It’s happening across strangers, sectors, care models, and technologies that were never designed to recognize one another.

And when accountability isn’t clear, exchange slows, not because technology failed, but because people are unsure who bears the risk.

What This Looks Like for Patients

Before we go any further, it’s worth grounding this in lived experience.

From the patient’s side, the reality often looks like this:

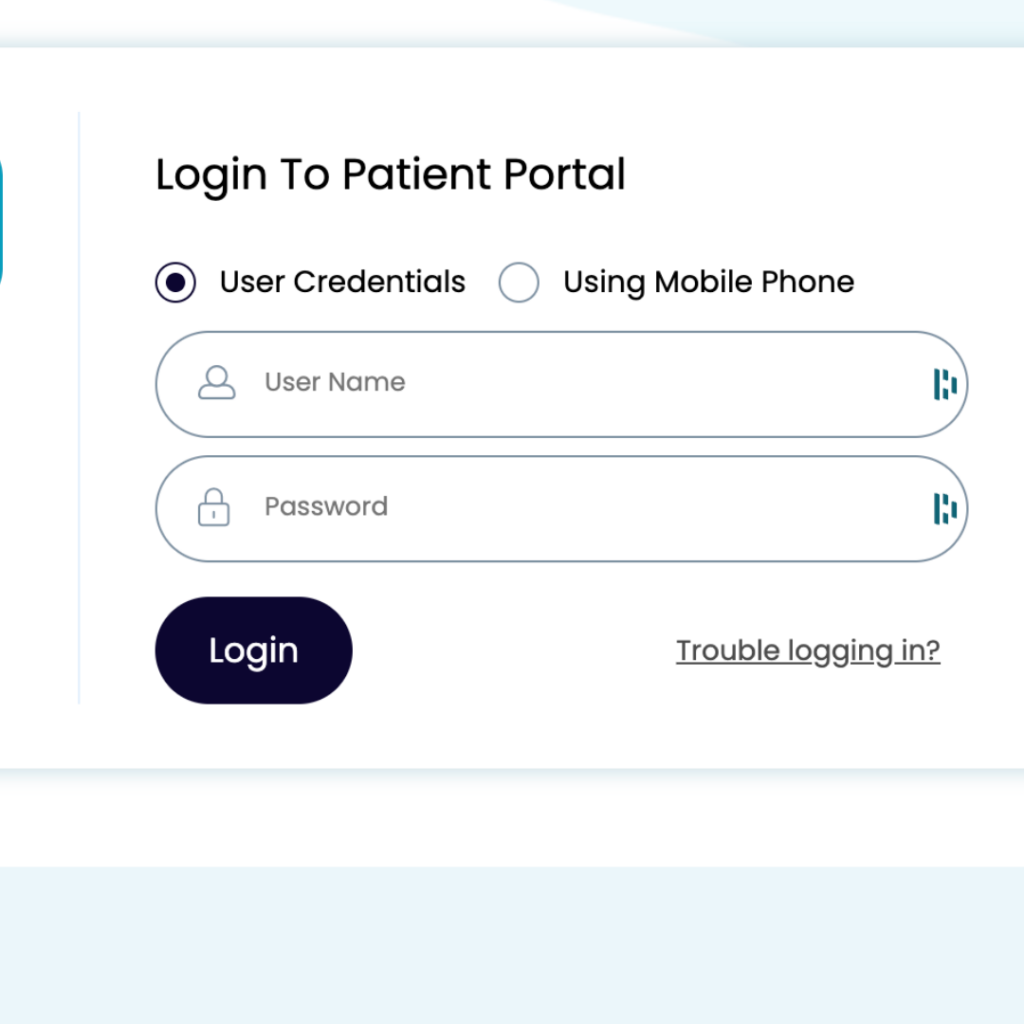

Multiple portals.

Forgotten passwords.

Fragmented records.

Repeated identity verification.

Shared passwords between family members.

Community providers with clipboards to gather health history, medications, and conditions.

Even with patient access APIs and TEFCA Individual Access Services, patients and developers are still left bridging across multiple models and dealing with inconsistent participation. The backend plumbing is largely invisible, but the friction is felt acutely by families trying to coordinate real care across real settings.

We’ve made it technically possible for patients to access their data.

We have not yet made it operationally simple, trustworthy, or something families can actually rely on.

Trust Breaks When Accountability Isn’t Clear

At a national scale, TEFCA’s promise isn’t just connectivity, it’s trust among strangers.

The framework was designed so organizations can respond to requests from entities they’ve never worked with before by establishing shared expectations, onboarding rigor, directories, and auditability. That applies not only to treatment-based exchange, but also to patient-directed access through Individual Access Services (IAS).

And yet, the same question keeps surfacing:

“Do I really trust who is on the other end of this request?”

That question shows up in different ways depending on the use case.

In treatment-based exchange, it often centers on interpretation:

- What qualifies as “treatment” under HIPAA?

- Who counts as a healthcare provider?

- Does a community paramedic qualify?

- What about a nurse care manager embedded in a nonprofit?

- If something goes wrong, who is accountable…me or them?

In patient-directed access, the question shifts:

- How do we know the patient is the one initiating the request?

- What about a family caregiver operating under proxy authority?

- What about an app, or an AI-enabled tool, acting on behalf of a patient?

- And once the patient shares their data, what are others allowed to do with it?

These are no longer edge cases. They are everyday realities for consumer-facing health technology in community-based care, EMS & mobile integrated health, rural health, and home-based models.

When the requester and responder don’t share the same assumptions, whether about treatment authority or patient-directed access, exchange stalls. Not because anyone is acting in bad faith, but because governance hasn’t kept pace with how data is actually being used beyond the walls of the healthcare system.

Trust doesn’t scale automatically.

It has to be designed.

Patient-Directed Exchange Raises the Bar

Conversations with builders working inside Individual Access Service (IAS) models have reinforced this reality for me.

In a recent conversation, Jason Kulatunga, CEO and founder of Fasten, was open and optimistic about where patient-directed interoperability is heading, but also thoughtful and cautious about how it works in practice.

That tension matters.

Centralized exchange models like health information exchanges (HIEs) and TEFCA make governance feel more tractable because participants are known, roles are defined, audit trails live in one place, and accountability has a clear center of gravity.

Patient-directed interoperability intentionally removes that center.

Data flows through patients, apps, families, and services that may never directly know one another. Authority becomes distributed by design. While that unlocks agency and access, it also makes traditional governance models harder to apply.

As Jason noted, the challenge isn’t inside TEFCA itself. It begins once data leaves the initial access point and moves into patient-directed sharing, where downstream recipients are no longer subject to the same regulatory or contractual obligations.

That doesn’t make governance less important.

It makes it more important and harder to get right.

When Data Leaves the System, Trust Stops Traveling

One of the hardest unsolved problems in patient-directed exchange is auditability.

Auditability is the degree to which health data can be verified, traced, and evaluated against established clinical, financial, and regulatory standards, ensuring information is reliable for high-stakes decision-making.

Adapted from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

In centralized systems, logging and oversight are relatively straightforward. Data flows are observable. Misuse can be traced. Enforcement has a clear place to land.

Patient-directed exchange changes that.

As data moves through patients, family members, apps, and AI tools, responsibility fragments. Maintaining visibility into downstream use becomes harder. Traditional audit assumptions no longer apply.

This isn’t a failure of patient access.

It’s a signal that our accountability frameworks were built for a centralized world.

This is also where the work of the CARIN Alliance deserves real recognition.

Through its Code of Conduct, CARIN Alliance has spent decades working to make sure patient data rights don’t vanish once data leaves an app or system, by asking vendors to contractually honor the same commitments regarding access, deletion, transparency, and secondary use.

That work matters. It reflects a serious, collaborative effort to establish shared norms in a rapidly evolving ecosystem.

But participation is voluntary. (Primary Record has signed on!)

And when downstream apps or services choose not to adopt those commitments, data can quickly become unauditable, not because anyone is acting maliciously, but because no enforceable governance follows it.

Trust, in other words, still stops too early.

If Trust Is the Constraint, What Actually Builds It?

As a nurse and health tech founder, this is the question I keep coming back to:

Is technology enough to solve a trust problem that is fundamentally human and institutional?

In every other critical infrastructure system — banking, aviation, energy — trust is reinforced through governance:

Clear authority

Independent oversight

Shared rules of participation

Disciplined onboarding

Auditability and accountability

Dispute resolution

Public transparency

Healthcare interoperability is no different.

If we want data to move safely across strangers, sectors, and settings, especially into homes, rural communities, mobile care, and family coordination, we need governance infrastructure that matches the complexity of the ecosystem.

Not just code.

Trust Is Built, Not Flipped On

One of the wisest things I’ve heard from health system leaders working inside TEFCA is that interoperability doesn’t arrive all at once.

Trust develops through use.

Organizations learn how others behave.

Patterns emerge.

Interpretations start to align.

Governance matures.

Confidence grows.

The mistake we keep making is assuming APIs can shortcut this process.

They can’t.

Only governance can.

An Open Question for the Care Ecosystem

So here are the questions I want to pose to policymakers, HIE leaders, health systems, startups, clinicians, and patient advocates:

Are we investing enough in the governance, accountability, and public trust infrastructure required for data to safely move across patients, communities, and care models at scale?

Is the next phase of interoperability less about building better pipes and more about building better trust architecture?

And, if patients are truly becoming active participants in interoperability, not just passive recipients, what governance do they deserve?

This isn’t a rhetorical question.

It’s a design challenge we need to solve together...now.